Back before fishing turned into a professional sport with boats that cost more than a double-wide, we had ourselves a tournament. We called it CARP—Carp Anglerings Rod & Pole—because it sounded official, and nobody wanted to pay lawyers to come up with something fancier. It wasn’t on TV, nobody had a sponsorship, and the only weigh-in station we had was a hanging scale from Ruby’s roadside veggie stand, and ain’t been accurate since Nixon resigned.

CARP was for folks who fished the way God intended: from a muddy bank, sitting on a bucket, with a sunburn forming somewhere creative. Our rules were strict, too. Bait was limited to frozen corn from the A&P. Not canned, not fresh, and certainly not “organic.” Only corn so cold it stuck to your fingers, and only from a store that smelled faintly like floor wax and broken dreams. Of course the S&H Green Stamps you earned shopping for bait was a bonus. We weren’t fancy people; we were faithful to tradition.

The heart and soul of CARP was Uncle Fat, who denied being ‘fat’, just “well-fed.” He was the kind of man who could outfish anybody, mostly because he spent more time napping than casting. He swore the best way to catch carp was to leave your line in the water, close your eyes, and let “the good Lord work it out.” Uncle Fat’s fishing pole was older than me, held together with black electrical tape, and bent permanently to the left, but it was lucky. He’d nod off in his folding chair, corn juice running down his shirt, and somehow wake up with a fish on the line.

Grandpa Ab, God bless him, had never fished a day in his life. Didn’t stop him from coming to every CARP tournament to “supervise.” He’d sit there in his old straw hat, sipping sweet tea, and offer encouragement like,

“If the fish wanted to be caught, they’d already be in your truck bed,”

“Ain’t no use rushin’ a fish. They got all day, and you forgot your patience at the bait shop.”

“Fishin’s like courtin’ — you sit quiet, look interested, and hope they bite before you say somethin’ dumb.”

Nobody dared point out he was sitting in the shade while we were cooking like bacon strips on a griddle.

Then there was Three-Finger Bob. The nickname tells you everything you need to know. He’d show up with a bucket, a length of fuse, and a grin that made you nervous. Bob believed dynamite was “just another lure, but louder.” I once saw him toss a lit stick into the creek, lean back like he was waiting on fireworks, and then scoop up a dozen carp like he was picking apples. Lost two fingers one day, but he swore it improved his casting accuracy. About two months before that fateful accident, the creek gained a new dirt dam because one of his throws was long and to the left – about six feet to the left. Blew a couple F150 long bed loads of dirt out of the bank and into the stream. Dammed up the creek and stopped water flow for two days until the little pond filled up and start overflowing.

Three-Fingers was only allowed to fish at least one mile down stream from the main tournament area. It was put up to vote at the pre-tournament meeting numerous times, the distance should be two miles. The vote was always close with some people claiming traditions should rule and it was traditional he only had to be one mile. Since Three-Fingers was not fishing with approved A&P corn, his catch never counted. But would still be cleaned and cooked at the town’s community center cook out later that night.

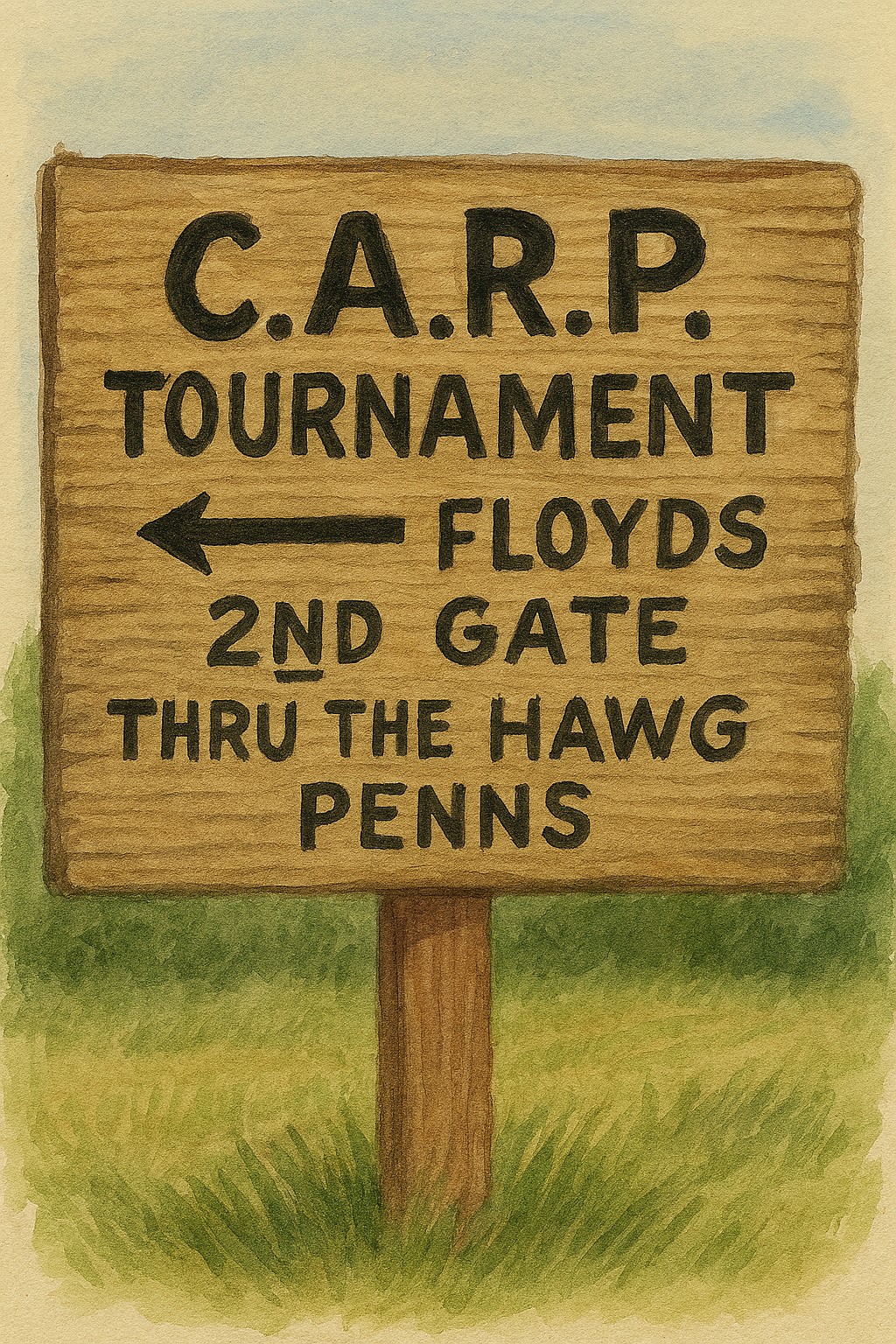

The “venue,” if you could call it that, was Uncle Floyd’s back pasture. Floyd was generous enough to let us use it because, as he put it, “That creek ain’t doing nothin’ but erodin’ my fence posts anyway.” But Floyd wasn’t one to make things easy. Getting to that back pasture was a rite of passage. First, you had to cross the front pasture, which was home to his hogs—twenty or so head of them, including two sows mean enough to make a grown man climb a tree. Floyd swore they were “gentle as kittens,” but we’d all seen those sows chase his own pickup like it was a chew toy. Once, Floyd slowed down a little too much and one of the sows hiding in a ditch, jumped up and hit his left rear tire so hard it broke the tire bead causing the tire to go flat. He didn’t stop to change the tire until he was safely back at his barn – even then after he changed his britches.

Once you made it through the hog gauntlet, you hit the middle pasture, which was patrolled by Floyd’s prized bull, a creature so hateful he didn’t even like Floyd. This bull had a particular vendetta against loud music, especially “that newfangled rap racket,” which meant every teenager with subwoofers had to cross with their truck stereo turned off and their fingers crossed.

Finally, if you survived the bull and the hogs, you reached the back pasture. That’s where the cows were. A couple dozen of them. Now, cows aren’t mean, but they’re nosy, and they think every human is a walking feed bucket. You couldn’t sit down to rig a line without three Herefords breathing down your neck, hoping for a handful of corn. Uncle Fat said that’s why carp fishing was so peaceful—“Once the cows start licking your hat, you forget about everything else.”

Tournament day was a scene straight out of a country fever dream. Pickup trucks lined the creek, every tailgate down, coolers open, and lawn chairs sinking into mud. Floyd’s hogs roamed the fence line like prison guards, and the bull stood at the far end of the middle pasture, glaring at us like he was taking names. Kids ran around with bait buckets, barefoot, daring each other to touch the electric fence (someone always did). Another fella tried thawing his frozen corn by holding it in his mouth, but forgot about it when a fish hit, and he nearly swallowed a handful.

That year’s winner was a kid who caught a carp so big it bent his pole like a coat hanger. We weighed it on the veggie scale, which said “Error,” so we just called it “thirty-ish pounds” and handed him a trophy made from a bent hubcap and some duct tape holding some broken fishin’ lures on to it. The picture we took looked more like a lineup of moonshiners caught by revenuers, but he hung that hubcap in his garage like it was a gold medal.

By sundown, we’d all hauled our gear out of Floyd’s pasture, chased the cows back through the fence, and bribed the hogs with a bucket of scraps so they’d let us leave in peace. The real magic of CARP wasn’t just the fishing—it was what came next. Every single carp (and a few other species thanks to Three Finger’s’dynamite) caught that day wound up at the community center in town. There the ladies’ auxiliary and half the volunteer fire department were waiting with fryers already hot.

By dark, the whole town smelled like hushpuppies and cornmeal batter, and folks came from miles around, pulling into the gravel lot with headlights bouncing off the trees. You didn’t need a ticket—just a donation and an empty stomach. The proceeds went to fund the fire department’s new hoses, turnout gear, or whatever truck part had fallen off that year.

And as the sun went down, the storytelling started. Under the glow of those buzzing yard lights, fish that had been “bout yay big” on the creek bank grew to the size of tractor tires. By the third plate of fried fish, somebody swore they’d hooked something that pulled so hard their truck slid toward the water, and nobody doubted them. The air got thicker with laughter, cigarette smoke, and mosquitoes so dense around the lights it looked like the fog was rolling in early.

We didn’t quit eating, swapping stories, and swatting bugs until the fryers ran low on oil and the fish pans were scraped clean. Everyone went home smelling like grease and citronella, full of fried food and tall tales that would only grow taller by next year’s tournament.

That’s CARP for you: a day of fishing you’d never forget, a night of eating you’d regret come morning, and a guarantee that somehow, somewhere, Three-Finger Bob was already scheming next year’s “improvements” to the creek.